42

Nuptials

The weather warmed a little, and Susan’s

wedding date duly arrived. If Lewis had expected to be able to spend some time

with his fiancée on the journey down to The Towers, he was disappointed. She

had the children and Iris Jeffreys in the coach with her. Lewis and Dom rode

alongside. Even though Mrs Urqhart had things well in hand at The Towers there

was an immediate hustle and bustle, and Lewis saw scarcely a glimpse of Nan

before the ceremony.

Daphne, who of course was chief bridesmaid,

had wanted Ditterminster Cathedral, but Susan had not desired such display, and

the ceremony was held quietly in the little village church at Dittersford, the

local vicar presiding. The wedding breakfast was at The Towers; and then Eric

took his bride quietly home to Willow Court.

Lewis discovered his fiancée sitting rather

wanly under a tree on the front lawn of The Towers that evening.

“Well, eet ees what she wanted,” she said

with a sigh as he sat down beside her.

“Yes, of course. And he’s a decent boy. He’ll

make her happy.”

“Yes. But eighteen ees so young.”

“Mm.” Lewis looked at her doubtfully. “I

think I see... You were less than that when you were first married, I think?”

“Yes, I was,” said Nan, frowning a little. “What

do you theenk you see?”

Lewis took her hand firmly in his. “I see

that you were forced by your circumstances to settle down and become a mère de famille when you were nothing

but a child. I also see that the deaths of both husbands must have been a

terrible experience for you, which cannot, I thank, have left you without

scars.”

Nan attempted to pull her hand out of his, “No,

I—”

Lewis held on. “The fact that you appear to

have coped magnificently with it all is beside the point. It is not your nature

to collapse in a crisis. That does not mean you feel nothing.”

“Well, no...”

“I think you married too young and had very

little fun in your life when you should have been having it.”

“Our household een India was nothing but

laughter and happiness,” said Nan in a voice that shook a little.

“Mm.”

“And—and I was vairy content weeth Hugo.”

“Mm.”

“I do not theenk I see what you are

implying,” she said shakily.

“No? Well, nothing very much, perhaps.

Merely that in spite of the opinions of persons such as your brother, most of

my relatives, and all of Society, I do not begrudge you the harmless amusement

afforded you by the company of such imbeciles as Vyv Gratton-Gordon, Haydock or

Charles Quarmby-Vine. Even though some of ’em are old enough to know better,”

he ended with a slight shrug.

“Oh.”

Lewis caressed her hand lightly with his

thumb. “But allow me to suggest that I—er—might be able to amuse you even more.”

After

a startled moment Nan snatched her hand away. “You weell do no such theeng! Eet—eet

ees to be a marriage of convenience, you know that vairy well!”

“Is it?” he murmured. “What if I said I do

not want a marriage of convenience?”

“Well, I—”

Lewis

watched unashamedly as her bosom rose and fell.

Eventually she said: “I see. Of course you

weesh for an heir: that ees only natural. You may rest assured that I weell do

my duty by you, my Lord.’

Lewis stood up, laughing. “Oh, Lor’, what an

awful thought! Heaven forbid you should do your duty by me, Nan!” He strolled

away, still laughing.

Nan gaped after him in consternation.

Mrs Urqhart and Dom had been interested and

unashamed spectators of this scene from her front windows. Her plump elbow

connected solidly with his ribs, and she went into a wheezing fit, gasping

through it: “Always knew there was more to that feller than meets the eye!”

Dom looked dubiously out onto the lawn. Nan

was still under the tree. There was now no sign of Lord Stamforth. “Er—aye. But

Mrs Urqhart, he’s lettin’ her get away weeth murder!”

“Is ’e?” said Mrs Urqhart, shaking all

over.

“Yes!”

Mrs Urqhart continued to shake all over, so

Dom, looking very cross, left her to it.

For the journey back Lewis begged Iris to

do him the favour of joining Miss Baldaya, Miss Gump and the little girls in

their coach.

This arrangement appeared to be news to

Lady Benedict. She certainly looked stunned when Lewis got into her coach. “Where

are the children?”

“They’re going with Miss Jeffreys and

Daphne. I wish to be alone with you.”

“But—”

“Johnny and Rosebud are with Nurse and the ayahs in the other coach: they will be all

right.”

“Yes, but—”

“Drive on, Hughes!” shouted Lewis.

Grinning, Mr Hughes touched his forelock,

and the coach set off.

“Luh-Lord Stamforth,” said Nan in a

trembling voice, “even though we are engaged, and—and my brother ees just out

there—”

“Actually, he ain’t: he’s helping your

Cousin Iris teach the girls backgammon; though how long he will last is anyone’s

guess.”

“Y—Oh, help. Um, well, even though he ees—ees

there, I do not theenk—”

“No, I know that, Nan: but it cannot signify,

we are to be married in less than six weeks. That’s what I want to speak to you

about.”

“Yes?” said Nan. swallowing.

Lewis smiled. “That’s a very fetching

bonnet, but why do you not take it off during the journey?

“Wuh-well, I— Yes, I would be more

comfortable weethout eet.” Uncertainly Nan removed the bonnet. It was a simple

straw, with a profusion of pale pink bows. She was wearing a pink pelisse,

which the modiste had assured her was entirely suited as carriage dress, over

which, for if it was a pleasant day, it was still only April, she had a warm

shawl. Lewis put his hand gently on hers where it lay on her pink knee. “Are

you warm enough, my dear?”

“Yes, thank you. Mrs Urqhart’s Bapsee has

given me thees nice hot breeck. Should you like a leetle of eet?”

Lewis did not need a hot brick to his feet:

his clothes were far heavier than hers. But he was not a gaby: he put his toes

on the brick next hers. This necessitated his moving up very much closer to her

and in fact pressing his thigh to hers. His affianced, he was interested to

see, went as pink as her garment.

He left his hand on hers, and said without

emphasis: “You are a woman, not an inexperienced girl. I think you must realise

that I desire you very much.”

“What?”

she gasped.

He pressed his thigh very firmly to hers

and put his free hand under her rounded chin.

“What are you doing?” said Nan faintly.

“What I rather think I have been a great

fool not to have done months since.” Lewis bent his head to hers and fastened

his lips gently to hers. He had a moment’s despair as she gave a tiny smothered

gasp and pressed herself back in her seat. Then her lips parted and she allowed

him to kiss her.

Eventually he sat back, panting. She had

not returned the kiss; nevertheless he was not altogether displeased.

“Oh!” said Nan, brightly flushed, lifting

her hands to her cheeks. “I deed not theenk that you—”

“That I wanted that?” said Lewis with a

smothered laugh.

“No, I mean that you— I deed not theenk you

were that sort of man,” said Nan limply.

He looked into her eyes. “Are you sure you

do not mean, the sort of man who knows the sort of woman you are?”

“No, I—”

Lewis smiled slowly, still looking into her

eyes. He picked up her hand, and undid the glove. Then he raised the hand to

his mouth, still looking at her, with a rather twisted little smile, and gently

kissed the inside of her wrist.

Nan shuddered all over and cried: “Oh! Oh, Lewis!”

Lewis at that wrenched her into his arms

and kissed her very thoroughly. This time she responded fiercely.

“Mm,” he said at last, releasing her and

flicking her chin with a careless finger. “Do you still think it will be

necessary to do your duty by me?”

“No,” said Nan, swallowing. “For—for you are horrid and—and not the person I

thought you were, at all!”

“I’m certainly not the lap-dog you appear

to have taken me for,” he said drily.

“No,” she agreed faintly.

He took her hand again, peeled the glove

right off, and slowly kissed the fingers.

“Lewis,” said Nan in a high voice: “I

really theenk eet—eet would be better to—to stop.”

“Don’t you trust me not to do something

shocking?” said Lewis wryly.

“No, I do not trust me,” said Nan frankly,

swallowing loudly.

Lewis smiled. He pushed his thigh hard

against hers.

“Don’t,” said Nan with tears in her eyes.

“I shall not be shocked,” he murmured.

“No, I am sure you weell not! But—but you

are pushing me to see how far I—I weell let myself go!”

“Perhaps I am, yes. Is that so dreadful?”

he said with a searching look.

“Yes,” she said faintly.

“I see. I thought it was something like

that,” he murmured.

“Luh-like what?”

“You do not wish to reveal to me—not your

true self, the self cannot be defined so facilely—but a very large part of the

true Nan. Or to reveal, indeed, very much of yourself to me.” Lewis leant his

head back against the squabs of the carriage. “When it is the case of an

unknown boy in your carriage with you—and I do know the whole, please don’t be embarrassed.

it is not my intention to embarrass or criticise you—when it is the case, let

us say, of two almost-strangers who need something very simple and very

straightforward from each other, you are not averse to showing that aspect of yourself.

Or when, at the other extreme, it is merely a case of silly flirtations in a

ballroom with a score of gentlemen who mean very little to you, you are not

averse to that, either. And in your marriages... Well, I shall not ask you to

talk about them. And of course you were only a girl when you married your first

husband. But I think it was a case of being sweet little Nan, very comfortable

to let herself be—guided, to say no more, by an older man. –Do not say

anything; I realise that a large part of that behaviour was perfectly genuine.

But not, perhaps, all of it; and not all of it with the second husband. And the

third does not want that.”

There was a long silence in the comfortable

carriage.

“I want... all. All of you. Without hiding

anything or pretending anything, or playing little games,” said Lewis

conversationally. “But not until you feel ready to give it.”

“You—you are quite eensufferable,” she said

in a low voice.

“What, in wanting to be married to the

woman herself, and not to one of the many personalities she assumes, as her

theatrical friends assume parts in their plays?” said Lewis with a tiny laugh. “I

think not! But as I say, as and when you are ready to reveal yourself to me.”

There was another long silence.

“And what eef the—the leetle games, or the—the

personalities were truly a part of the real me?” said Nan in a trembling voice.

“Oh, I think they are. But there will

always be times when the opportunity is there for you to play a part, but if

you love me and wish—not to please me—to be honest with me and, well, not to

hurt me, I think is what I mean, au fond:

yes, not to hurt me, then you will not take the opportunity.”

“Buh-but—what times?” she faltered.

“I cannot say. I think that understanding what

those times are, is something that comes with time and with caring itself.”

“Ye— But that ees contradictory, Lewis!”

she cried. “I try to picture eet een my head, and—and eet goes round een a

circle!”

“Mm. You are applying reason, my dear,

where I think it is, rather, a question of sentiment.”

“Sentiment,” said Nan, frowning over it.

“Mm.” Lewis sat back and stared vaguely out

of the window for a long time. He was still conscious, however, of the

pleasurable sensation of her thigh against his. And also conscious of the fact

that she did not pull away from him.

At the first change Johnny made a great

fuss over getting into the carriage with the two of them. Rosebud became

jealous and insisted on coming, too. Lewis raised no objections: he could see

that he had given Nan much food for thought.

They took luncheon when they next stopped

to change horses: the little ones became somnolent and allowed themselves to be

returned to their nurses. Lewis got back into Nan’s coach without saying

anything. The day had warmed: it was a fine afternoon and there was certainly

no need for a hot brick. Nevertheless he sat very close to her again, and again

pressed his thigh to hers.

He could feel the tension in her.

Eventually he said with a laugh in his voice: “Take the damned bonnet off!”

“What? Oh.” Nan removed the bonnet. Lewis

took it from her and chucked it onto the seat opposite. “What is it?” he

murmured.

“Nothing,” she said, licking her lips

nervously.

“I think it is not nothing.” He took her

hand gently and began to ease her glove off. “Perhaps I did not perfectly make

it clear that there is no need for hypocrisies, with me?”

She swallowed loudly and did not speak.

Lewis removed the glove. “Your hand is warm and sticky: give me the other.”

She let him take the other glove off, too.

Lewis took both little hands in his and

turned them palm up. They were ridiculously small and pink. He buried his face

in them.

After few moments his fiancée said in a

very high voice: “Lewis, please would you kiss me again?”

Lewis looked up, smiling, though his heart

was beating very fast. “There could be no objection to that! But I think that

possibly what you mean is, might you kiss me?”

She nodded jerkily. “Um—yes.”

“I should like that.” Lewis leant his head

back against the upholstery and looked at her expectantly.

“You—you are making eet vairy hard for me,”

said Nan in a confused voice.

“No!” he said with a choke of laughter. “It’s

doing that for itself, my dear!”

Her eyes went very round and she turned

deep scarlet.

He smiled, grasped her arms gently, and

pulled her towards him. Nan put her hand timidly on his shoulder. “Kiss me,” he

said, sliding his hand down her arm.

She put her lips timidly on his. Lewis

grabbed her wrist, clapped her hand to his member, and pulled her on top of

him, kissing her until they were both breathless.

“Oh!” gasped Nan at last.

“Mm: ‘oh’.” Lewis showed her the tip of his

tongue. She went scarlet again: very gratifying. “Go on,” he murmured, putting

his hand on top of hers.

“Do you—do you really want thees, Lewis?”

she said huskily,

“Yes!” replied Lewis with a laugh. “Ain’t

it obvious?”

“Yes—only—” She looked at him anxiously.

“Can you not believe that I want your hand

there even more than you do? Or is it that you cannot believe what a dirty old

fellow I in fact am?”

Nan bit her lip. “Well, um, both,” she said

in a choked voice.

He saw with relief that she was now trying

not to laugh. “That’s better!” he said, touching his tongue to the tip of that

entrancing little straight nose. “Well, I am a very dirty old fellow, but I

suppose I shall just about be able to exercise sufficient restraint to remain

within the bounds of—er—gentlemanly behaviour, until our wedding night.”

Nan gulped, and nodded.

“Well, there is always the risk that

something might happen to me before we could be wed, and that you might

conceive,” he said gently.

“Yes. –There are ways,” she said very

faintly.

“Yes, ma’am!” said Lewis, laughing. “But, I

hate to disillusion you, I fear that just at first, y’know, I may not have the

self-control to practise ’em!”

“Um—no!” said Nan, swallowing a laugh and

peeping at him. Lewis smiled and touched the tip of her nose with his tongue

again.

“Lewis,” said Lady Benedict through her

teeth: “eet drives me near to screaming when you do that.”

“You are not alone in that, and thank God

we are both admitting it at last! Speaking for myself, I’ve been in agony ever

since that first night I met you at George and Mary’s. –Don’t say anything, I

know you barely noticed I was alive.”

“No: I—I was eentrigued by that—that dark

look of yours,” said Nan in a low voice.

He pulled her very tightly against him, so

that she was virtually lying on top of him. “I’m glad to hear it. And now, ma’am,

can you get me out and do me? Because I don’t think I can last out the rest of

this damned stage.”

Forthwith she got him out of his breeches

and did him very nicely.

Lewis lay back against the upholstery,

panting.

“I love you, Lewis,” said Nan with tears in

her eyes.

“No,” he said faintly. He panted for a

little. “Not yet, you don’t, Nan. But you love my masculinity, that is a start.”

She

swallowed. “Is it? Mm.”

“Come here and give me a nice kiss,” he

murmured. When she did he pulled her on top of him and simply slid his hand

between her thighs. Lady Benedict’s reaction to this outrageous move was,

frankly, extremely gratifying.

… “I suppose that was vairy naughty,” she

said, quite some time later, still sprawled on top of him.

“I’d say it was quite natural,” said Lewis

mildly, kissing her curls.

“Ye-es.” Nan looked anxiously into his

face. “You are truly not shocked?”

“Not at all. I happen to think a woman

should be like that, Nan. Prunes and prisms have never appealed to me.”

“No-o... What about modesty?”

“True modesty is admirable but boring.”

“I see,” said his fiancée faintly. “I

theenk I deed not know you at all.”

He laughed, set her upright against the

seat cushions, and gently straightened her dress. “If you can think of some

place we could be together without fear of being overheard, I might do

something even nicer for you next time.”

“I—I cannot, actually,” said Nan weakly. “Um,

perhaps eef you were to drive me to, um, Richmond or some such, and we were to

have a picknick?”

Lewis raised his eyebrows. “With you for

dessert? I would not be averse! Er—what about the coachman?”

“I was theenking you might take your

curricle.”

“I don’t actually own— You mean I might buy

a curricle?”

“Eet ees something that you could use,” she

replied simply.

He shook for some time, finally gasping: “Might

I ask how many gentlemen— No, I suppose that’s unfair. You might well ask me,

how many ladies.”

“I— Well, I do not mind telling you, eef

you are not going to be cross?” He shook his head, looking wry. “We-ell...

there was one drive last Season weeth—weeth Captain Quarmby-Vine. He—he ees not

so good-looking as Commander Sir Arthur Jerningham, but—um…”

“Less of a gent,” said Lewis drily. “Well,

my dear?”

“Um, we had been to see one of hees sisters

and—well, there was a leetle park, and we went for a stroll, eet was a vairy

warm day. And hees sister had fed us on great amounts of cake and sandwiches.

So we sat down under a tree for a leetle. And he said he was very full of cake

and lay down. And, um,” she swallowed: “I could see he was vairy interested:

one cannot help seeing.”

Lewis nodded calmly.

“And then he, um, undeed hees breeches.”

“Because of the cake.”

“Mm. He saw I was looking, so he said ‘There

ain’t much room een these, at times.’ And I said: ‘No, eet cannot be easy for a

man.’ And he said: ‘Eet could be eased, though.’ And sort of looked at me. Then

I yawned and said I was really vairy sleepy and he said to just close my eyes

and—and perhaps we could both be eased. And put hees hand on my leg. So I—I

sort of closed my eyes.” She looked at him anxiously.

“Go on,” said Lewis, shaking slightly.

“Oh, you are not cross!” discovered Nan in

tremendous relief.

“Of course I’m not cross, but I confess I

am intrigued: would not have thought Charles had that much nous!”

“No, nor I. Um, well, he put my hand on

heem. I steell had my eyes shut. And then he pulled my dress right up, and—and

teeckled me, a leetle.”

“Very enterprising,” said Lewis on a grim

note.

“And—and then he said eet was vairy hot and

thees would be cooling and—and—you know. He, um, turned round,” she said,

swallowing hard.

“In a public park?” croaked Lewis.

“There was no-one around. And afterwards he

lay vairy close and just let me rub eet. Well, he deed shout a lot, but there

was no-one to hear. And then he said he would be my slave forever.’

Lewis was sure he’d said so: yes! He

managed to croak: “I see.”

“I haven’t told anyone else,” she said

anxiously.

“No,” he croaked.

“Um—he deed do eet one other time, but eet

was a long time before we were engaged, Lewis.”

“I think you had better tell me,” he said

with a sigh, “or I’ll spend the rest of my life wondering about it!”

“Um—yes, that’s what I thought. Eet was

vairy sad, really. We were at a card party. Dom went off weeth hees friends,

and Mrs Urqhart had a headache. So Mrs Quarmby-Vine, hees sister-een-law, said

she would see me safe home. But when the Captain and I had finished our hand of

piquet, she had gone; at least, we could not find her. So he took me home. He

was vairy proper and said as soon as we got eento the carriage that I had

nothing to fear from him. So of course I said I knew that and that he was one

of the nicest men I knew. And he was looking vairy, vairy sad. so I put my hand

on hees knee. And then he cried a leetle, and—and went down on hees knees, and

said he knew he deed not have a hope but eef the opportunity ever arose he

would fight a duel for me, also.”

Lewis’s jaw dropped, but the narrator

apparently did not notice.

“And he put his head in my lap. And I said

I thought he had better not. And he said een a vairy, vairy sad voice: ‘Just

the once; we may never be alone together again.’ And he slid my skirt up and

put hees cheek against my luh-leg.”

Lewis swallowed involuntarily.

“I could not reseest, I wanted eet so much.

I am not trying to excuse myself: I was not engaged to heem and—and not een

love weeth heem, there ees no excuse at all. I am just telling you that—that

ees how eet was.”

“Mm,” he said, patting her hand. “I know.”

Nan sat back, sighing. “Actually eet was

vairy eenteresting, he rubbed heemself at the same time, I had not before seen

that.”

“Er—no. I see. Poor damned Charles, no

wonder he’s been following you about like a lost spaniel! Er—do I have the

time-frame right: this last was after the affair with Pom-Pom?”

“Um, yes,” she said nervously.

There was a short silence.

“You were eegnoring me!” she burst out.

“Yes. Hush. I’m a damned idiot, I suppose,”

said Lewis, squeezing her hand very hard. “Look,” he said, frowning: “the thing

is, Nan, I’m in no doubt I could have given it to you then. But I—I suppose I

didn’t want it upon those terms. We might never have got to know each other as

two human beings who might build a life together, rather than as two simple

animals who merely needed each other.”

“Yes. I see. Do you theenk we might build a

life together?” said Nan in a tiny voice.

“I hope so. I shall try.”

“So shall I.”

“And any time you feel like having—er—a

little relief in your carriage, pray do just mention it: I should be happy to

oblige,” said Lewis with a laugh in his voice.

“Now you are teasing,” said Nan resignedly.

“No! I mean it.”

There was a short silence.

“Mm?” he said, raising his eyebrows.

“Sometimes a gentleman finds eet awkward

and—and embarrassing, eef a lady, um, makes demands upon heem.”

“Eh?”

he said with a laugh.

“No, truly.”

“Er… did one of your husbands have trouble

performing his matrimonial duties when required?”

“No, eet wasn’t that. But eet deed

embarrass John, even eef we were quite alone, eef I showed heem that I—I

weeshed for eet, unless we were een our bedroom.”

“I’m not like that,” said Lewis mildly.

“No-o... And Hugo sometimes kissed me een

the carriage, but once when I, um, weeshed for more, he became quite cross and

said there was a time and place for everything.”

“I am not like that, either.”

“No-o... He was vairy robust,” said Nan

with a sigh, “but also vairy proper. And I deed sometimes feel that I would

never be able to live up to his standards.”

“I see. I don’t wish to criticise either of

them, my dear: very many men are like that, when it is their wives in question.

Many people would say it is most proper and commendable.”

“Yes,” said Nan glumly.

“We Vanes, however,” said Lewis pompously

in the voice of his Cousin Tobias, “would say it was demned bourgeois and borin’.”

Nan gulped, failed to control herself, and

went into a fit of helpless laughter.

“That’s better,” said Lewis, smiling, and

patting her knee.

Not altogether unexpectedly his fiancée

then burst into a storm of sobs, casting herself into his arms.

“It’s all right, Nan,” said Lewis at last. “Now,”

he said, giving her his handkerchief, “do not for God’s sake give me any

protestations of either devotion or fidelity.”

“But—”

“Can we just both agree to try? And to try

to be honest?”

“I can try,” said Nan faintly. “I theenk

for me honesty ees—ees more difficult than fidelity. I was never unfaithful to

John or to Hugo. But een other matters, I—I was not always honest.”

Lewis swallowed a sigh. “Mm.”

“You… I theenk you may be asking too much

of me,” she said anxiously.

He had come to realise that, more or less,

these past few months. “We’ll see. I can put my foot down, if I have to. I

rather hope I shall not have to.”

“Mm,” said Nan on a glum note.

“Well?” said Mrs Urqhart.

Lewis pulled a face. “Well, I’ve

demonstrated to her in no uncertain terms that my instincts are, shall we say,

as strong as her own.”

“That’s good!” she said, shaking.

“Mm. And—er—I warned her that I can put my

foot down, but I hope I shall not have to. She did not appear entirely

comforted by the news.”

“Aye... Well, it weren’t news, deary, she

ain’t that thick. Um—no, the thing is, I know you’re hoping she’ll see for

herself when she’s hurting you by encouraging all these idiot hangers-on.”

“Yes,” said Lewis shortly, reddening.

“But... Now, don’t take this amiss. She ain’t

a little girl, but she is a lot younger than you, and she is used to older men.

I think she may need you to put your foot down occasional, Colonel. –Drat! Your

Lordship.”

“I really think you had best call me Lewis,

ma’am, if you would care to!” he said with a laugh.

“Well, I’d like to, and that’s a fact! Um—what

I’m trying to say, there’s something in her nature what may need it, Lewis!”

“Er—oh, good Lord. That may need me to—uh—come

the heavy father?”

“Exact.”

Lewis bit his lip. “Have I been taking the

wrong tack all these months, Mrs Urqhart?”

“No, acos if she’d started to see you as a

soft old daddy like General Kernohan, she wouldn’t never have looked twice at

you. Well, she’s a woman as needs a strong hand, it’s what I’ve always said. She

ain’t the sort that’s been a grown-up, sensible woman ever since they was aged

about ten. But I ain’t never heard as you’re a feller what’s ever fallen for

them calm, mature types,” she said shrewdly.

“No.” Lewis thought of the tempestuous

Violetta Spottiswode, and smothered a laugh. “No! How true.”

“That Rani thinks you’ll have to beat her

after you is wed, but I wouldn’t go that far,” said Mrs Urqhart comfortably,

heaving herself up. “I s’pose if I’m to look respectable at St Whosis, Hanover

Square, I better go and be fitted for me blamed dress.” She looked up at him

hopefully.

Smiling, he bent and kissed her cheek. “You

should be giving her away, you know, dear ma’am!”

Mrs Urqhart gave a horrible wink. “Aye, but

I ain’t so pretty as Francis Kernohan!”

Lewis went into a strangled paroxysm, and

she sailed off, looking very pleased with herself.

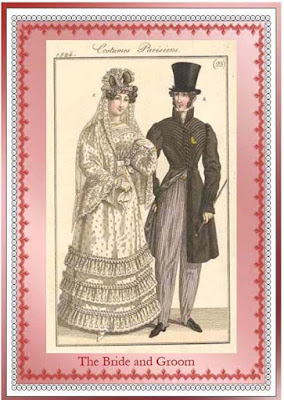

The wedding of Lady Benedict and Viscount

Stamforth at St Whosis, Hanover Square, in early June was one of the events of

the Season. Those who normally got out of London before the warmer weather was

upon them stayed on for it. Many who normally were not seen in London for the

Season at all made a point of coming up for it.

Miss Iris Jeffreys had been a bridesmaid,

but very fortunately a certain charming informality prevailed in the

arrangements for seating at the breakfast, and she was able to avoid the top

table, not to mention the conjunction of the personalities of Her Grace of

Purle, Mrs Vane, and Aunt Kate, and escape to more congenial company.

“It’s hard to say, really,” noted Lilias

languidly, eating a savoury puff, “which is more bridal: the actual bride, the

chief bridesmaid, the Duchess, or Lady Georgina Claveringham. –Who the Devil

invited her? I didn’t think Nan knew her, and I’m dashed sure she ain’t a close

friend of his!”

“Ssh!” hissed Iris, shaking. “Her Grace of

Purle invited her, out of course. In fact she was almost entirely responsible

for the guest list. As I really do think you might have guessed, Lilias,” she

added severely.

“I apologize humbly.” Lilias looked at Lady

Georgina in primrose lace. “The dashed monkey’s in primrose, too!” she gulped.

“Hullo,” said a deep voice, in suspiciously

meek tones, while Iris was still splutteringly helplessly. “May I sit with you?

I don’t know all these fashionables.”

Iris nodded feebly, and Major Norrington

drew up a chair. “I’m Major Norrington,” he said simply to the yellow-haired

young lady.

“Hullo,” replied Lilias calmly. “I’m Lilias

Jeffreys, Iris’s cousin.”

“First cousin once removed, if we’re

counting,” said Iris on a dry note.

“We were just discussing the ladies’

dresses, Major!” Lilias explained brightly.

Iris cringed, but Ursa Norrington replied

calmly: “Then don’t let me stop you, Miss Lilias.”

“Thanks. –Did you get a close look at that primrose

spencer-arrangement of Lady Georgina’s?” she asked Iris. “Mere wool?”

Giving in, Iris admitted: “No. Velvet,

trimmed with swansdown. The thing hanging from it is some sort of a foreign

order on a purple ribbon. But it is not a spencer, but an abbreviated jacket.”

“I stand corrected,” she said solemnly.

“The hat’s good,” offered the Major meekly.

Lilias agreed cordially: “Yes, if one

defines ‘good’ as possessed of giant ostrich feathers that have by a

conservative count severely embarrassed two noblemen of the rank of duke, one

of the rank of marquis—did you see Rockingham sneeze when they got up his nose?—three

earls, and countless barons.”

“Fluffy,” he said vaguely.

“Lilias, do not try,” warned Iris as she

opened her mouth again.

Lilias looked uncertainly at the Major.

“Two of the rank of marquis: the tall,

stout fellow over there is Wade,” he said unemotionally.

“See?” said Iris.

Lilias ignored this, and looked

thoughtfully at the Marquess of Wade’s table. “The G.-G.’s seem to have been

joined for the occasion by half the Spottiswodes.”

“Mm? Oh—yes.” Uneasily Iris eyed a small

pink thing on the Major’s plate. “I wouldn’t touch that pink thing, Major.”

“In for a penny, in for a pound,” he said

cheerfully, popping it into his mouth. A startled look came over his face, but

he continued to chew.

Wincing, Iris tasted a piece of pie.

Pigeon? At this season? Oh, well! “Spotton is the one with the hopelessly

dreamy look on his face,” she noted helpfully.

“Lady B.—Lady S., I should say—may well

have met him back when he was Lord Lytton-Howe: he was out in India for some

years,” contributed Major Norrington.

“Or not,” said Lilias. “Iris, wake up! You

must have heard!”

“Eh?”

“Lady Algie Spottiswode!” she hissed.

“Mm? Oh, yes, sitting with Lord Billy G.-G.

Well, that is to be expected. And his Pa and Ma don’t seem to be objecting.”

Lilias rolled her eyes in despair.

“Shall I tactfully disappear?” asked the

Major.

“No, but you could tactfully get me

something edible, if you will, Major,” said Iris with a sigh.

Grinning, the Major took her plate and, as

an afterthought, Lilias’s, and wandered off.

“Look, whatever you’re trying to say, just

shut it: he’s Stamforth’s closest friend!” said Iris angrily to her first

cousin once removed.

“Oh, so you truly do not know?” she said,

brightening. “Lady Algie—Violetta Spottiswode—was one of Stamforth’s. A few

years back, true. Before she decided

she liked ’em really young. Well, she was under forty back then.”

Iris swallowed. “Help. Does Nan know?”

“Why should she care? She’s the woman in

possession.” Lilias looked thoughtfully at Nan, radiant in fluttering white

lace over pink silk. The delightful hat was trimmed with orange blossom—silk,

one presumed—and quite possibly tuberoses. “She seems to have got over her

doubts: I never saw an expression of more indecent triumph. It’s beyond me what

he’s got to provoke it. Besides one of the oldest titles in England, of course.”

“Stop it,” said Iris grimly.

She peered. “Are there actually lace

ruffles on those lace ruffles, or is

it my eyes again?”

Iris sighed. “Very well, I’ll tell you, but

you won’t like it. Every second

little lace flower has another little lace flower over it, attached loosely

with a few odd seed pearls. That’s what’s making the petals seem to flutter:

they not only seem to, they do.”

“Don’t go on,” she said sourly.

“Not everybody can wear pink,” added Iris

detachedly.

“How true,” the yellow-haired Lilias agreed

bitterly. “Although Daphne is not one of ’em. And why, talking of Daphne, did

she let you get away with that admittedly luscious deep blue silk?”

“Ssh!” she said, laughing. “Her Grace of

Purle having decreed that the bride’s attendants should be like a bed of

many-coloured flowers, Daphne decided that I should be a tall, deep blue”—she

looked at her sardonically—“iris.”

Lilias choked.

“Serves you right,” said Iris with

satisfaction.

“Is she choking to death?” asked Major

Norrington, returning with laden plates.

“I sincerely hope so! –Thanks, Major,” said

Iris, sighing. “This looks like real food.”

“Yes; I found an English butler. He was

most sympathetic.”

Iris embarked on it gratefully. Lilias also

embarked on it but asked airily: “Have you remarked that the bride’s attendants

form a bed of many-coloured flowers, Major?”

“Certainly,” said Major Norrington

instantly. “We have a pink daphne

bush, of course, and a deep blue iris;

and though I had not heard of a pale yellow cherry

blossom heretofore, I am willing to admit—”

He stopped: Lilias was choking again.

Iris banged her on the back, a very dry

look on her face. “I told you what he was like.”

“Yes!” gasped Lilias helplessly. “So you

did.” She drank some champagne and said with a grin: “Sorry, Major.”

Major Norrington’s broad face was, for

obscure reasons, wreathed in smiles. “That’s all right.”

Lilias smiled at him, but after a moment

noted to her cousin: “The cherry blossom doesn’t look too bright. Or is it my

eyes, once more?”

“No. Been bawling,” said Iris gruffly.

Lilias looked over at Sir Noël. She swallowed. “Amory,” she said

in a high, faraway voice, “is sitting with Lady Hartington-Pyke. And the lady

next her, who gives every impression of being her bosom bow, and for all I

know, may well be, is Lady Ivo. She and Sir N—”

“Yes,” said Major Norrington calmly. “I did

wonder why Her Grace of Purle invited the pair of ’em, but I’ve come to the

conclusion there are two reasons: one, to leave them out of the biggest Society

wedding this century would occasion more remark than to include them in; and

two, she’s a spiteful little old cat.”

The cousins smiled limply. After a moment

Lilias manged to admit: “In a nutshell.”

The Major merely looked dry.

“Phew!” concluded Mrs Urqhart, waving the

coach off vigorously.

Bobby smiled a trifle wanly. “Aye. Never

thought we’d see the day, hey?”

“No,” she said simply. “You having regrets?”

“No.” He looked after the coach, and bit

his lip. “Not in that direction, no.”

“Catriona’s in Scotland,” said Mrs Urqhart

unemotionally,

“Yes,” said Bobby in a stifled voice.

“And you’re a fool,” concluded his cousin.

“Mm.”

They were silent, whilst around them surged

a mêlée of waving guests, departing guests, guests deciding not to depart just

yet, and guests making definite appointments which no-one particularly believed

would be kept, to meet later in the summer at this, that or the other watering

spot or country house.

“I was intendin’ to go down to Cowes,”

noted Bobby glumly.

“More fool you.”

He took a deep breath. “Betsy, will you

give me Mrs Stewart’s address?”

“Yes. Come on, you can take me home, I’ve

had enough of this lot.”

Surprised but not unwilling, Bobby ordered

up his cousin’s carriage and assisted her into it. “Are you feeling quite the

thing, Betsy?” he said cautiously.

Mrs Urqhart sighed. “Aye. Well, I kept

feeling it would never come off.” She pulled a face.

“Personally, I was expecting a thunderbolt,”

agreed Bobby sympathetically.

“Aye.” She stared vaguely at the street. “Be

good to her, Bobby.”

Bobby reddened, but said steadily: “If she

will have me, I have every intention of being good to her.”

“Glad to hear it. But I meant— Well, that

husband of hers was a dead loss, far’s I can gather. She ain’t one to let on to

another woman what went on in her marital bed, but—” She shook her head.

“I’ll do my best,” he said meekly.

“I’m telling you that you’ll need to treat

her gentle as—no, more gentle than—a virgin what don’t know nothing!” she said

loudly and angrily.

“Er—yes. I see,” said Bobby slowly.

“And if that’s put you off the whole idea,

you can get out of this carriage here and now!” she said furiously.

“No! Good gad, no! Surely you don’t have

that low an opinion of me, Betsy?”

“No. Sorry,” she said sheepishly, patting

his knee.

Bobby squeezed her hand gently.

Mrs Urqhart’s grasp tightened on his. She

stared at the street for a long time, not speaking.

Finally, as the barouche drew up, she said:

“Dare say this spat of Noël’s and Cherry’s is something and nothing, hey?”

“I’m quite sure it is. Cherry wished Viola

to come up to town for today’s affair and Noël didn’t.”

“You mean Viola and Cherry wished Viola to

come,” she said drily.

“Mm. Added to which, they’ve had a row over

what the first infant should be called if it’s a girl. –No, she ain’t, yet,” he

said as her face brightened.

“Oh,” said Mrs Urqhart sadly.

“Noël is adamant against ‘Viola’,” said

Bobby blandly, handing her down.

She choked, and grabbed at him wildly for

balance.

“All right?” he panted, steadying her.

“Yes! And you ought to know better than to

come out with somethin’ like that when I ain’t steady on me pins! Come in, we’ll

have a decent cup o’ tea.”

“Thank you,” said Bobby gravely, conducting

her indoors.

“So?” she said, collapsing onto a sofa with

a sigh. “—Chai, ekdum!” she shouted

at her son’s butler.

“Oh: my putative great-niece!” said Bobby

with a laugh. “Cherry thinks ‘Violet’ would be a suitable compromise. She made

the mistake of telling him it was a sweet name and that his objections were

illogical.”

Mrs Urqhart looked at him wildly. He shrugged.

“Lor’. Glad I’m not young again,” she said

frankly.

Bobby laughed and sat down beside her. “Me,

too!”

“Noël was her idea,” she said

reminiscently.

“Eh? Hers and Mallory’s, surely, old dear?”

he said, grinning.

Looking pleased, Mrs Urqhart patted his

handsome thigh. “No! –Best leg in London,” she murmured to herself.

“Thank you, Betsy,” said Bobby in a weak

voice.

He got up to go, straight after the tea

tray: he could see she was tired. “May I

hug you, Betsy?”

“Out o’ course!” she said, struggling to

her feet, her round face all smiles. “You great noddy, you may hug me any time!”

Bobby forthwith hugged her very tight. “We

all owe you a lot, Betsy,” he said huskily.

“No, well, I allus did enjoy a good plot,”

she responded calmly, hugging him strongly.

“Mm,” he said, sniffing slightly.

“Now, don’t get mawkish on me,” said his

Cousin Betsy firmly. “You get on up to Scotland!”

“Yes, I shall.” He kissed her cheek gently,

but Mrs Urqhart took his handsome face firmly in her hot, plump hands, and

planted a smacking kiss on his lips.

“There!

Be off with you!”

Smiling shakily, Bobby took himself off.

Mrs Urqhart tottered back to the sofa. “Lumme,”

she said to herself in a feeble voice. “I feel all of a doo-dah. Never thought

he’d go and do it. Well, him and some others!”

She lay down, yawning. “I’ll just close me

eyes for forty winks or so,” she muttered, closing them.

“...Dratted Noël,” she mumbled. “Never did

know a good thing when ’e was—” She yawned. “Onto it. I’ll sort ’em out

termorrer,” she concluded, drifting off.

No comments:

Post a Comment