38

In

Which Cherry Is Determined, & Noël is High-Handed

Daphne and Susan were still out, doubtless

enjoying the fresh air and freedom after a week cooped up in the house. Cherry

and Iris were in the girls’ little upstairs sitting-room, Cherry on the

window-seat.

“That is odd,” she said in a low voice.

Iris was trying, without much success, to

concentrate on a book. “Mm?”

“Sir Noël has just come out of the house.”

“I dare say he is after a breath of fresh

air.”

“No: out of this house, Iris!”

“What?”

They stared at each other.

Finally Cherry, very flushed, said: “I

suppose Nan sent for him.”

“Why in God’s name would she do that? On the

one hand, she scarcely knows him, and on the other, I don’t think she much

likes him. And to introduce a third hand into it, the last time she saw him,

wasn’t he being bundled into a hamper?”

“Um, yes.”

“Then she’d be potty to send for him. You

may well say she is potty, but—”

“Don’t be absurd!” said Cherry crossly.

Iris’s eyes twinkled but she replied

politely: “I beg your pardon. I think perhaps Lord Stamforth must have sent for

him.”

Cherry stared. “Why?”

“I have no notion. Possibly he wished for

male support at this trying time?”

Cherry got up, pouting. “I shall ask him!”

“Mm, well, that would be one way of finding

out,” she murmured.

Cherry hurried out, very red.

“Nose out of joint,” discerned Iris.

“Serves her right for turning down a good man.” She made a very sour face, and

picked up her book again.

“Sir—,” began Cherry.

“Yes?” said Lewis politely.

“Um—did Sir Noël Amory come to see you?” she

asked in a tiny voice.

“Well, yes; I am afraid I asked them to let

him into the house, Miss Chalfont,” he said apologetically.

“Mm.”

Lewis realised what must be wrong. He

repressed a smile. “We had considerable news to exchange. No doubt he will ask

if he may see you, the next time he comes.”

“Yes,” said Cherry in a tiny voice, looking

as if she was about to burst into tears. “Thank you.” She hurried out.

Smiling a little, Lewis sat down to await

Kettle and some clothes.

“That is Kettle!” gasped Cherry. “What can

he be doing here?”

“Go downstairs and find out,” said Iris

with a sigh, not asking who the Devil Kettle was.

“No,” she said, reddening.

Iris shrugged.

… “Iris, Lord Stamforth is going away!” she

gasped.

Unceremoniously Iris joined her at the

window. “Clad. Possibly the Kettle fellow brought him some clothes?”

“Um—yes. Um—he is Sir Noël’s man. Um—that will

be it.”

“Mm. I wonder if Nan knows he’s gone?”

Cherry looked at her fearfully.

“I’m not volunteering to tell her,” Iris

decided.

“She was crying, earlier.”

“I heard her!”

“Well, I—I think I should go to her,” she

ventured.

Drily Iris reflected that if Nan wished to

bawl again, Cherry would deal with it far more sympathetically than she could.

She merely nodded.

Looking doubtful, Cherry went out slowly.

“I am perfectly all right,” said Nan

grimly, sitting up and blowing her nose.

“Yes. Good,” agreed Cherry wanly.

“Lord Stamforth has gone to an hôtel.”

“I see.”

“And you are going to Merry and June.

Please pack.”

“I shall not desert you, I do not care if

you are horrid to me!” she cried.

Nan bit her lip. “I do not weesh to be

horrid, but you should not be here.”

Cherry took a deep breath. “I am going to

take Pug for a walk. I shall call on June, for I intend telling her everything.

And then she and I will walk back; and I will let her in, you do not have to

see her, but at least the square will think she is paying a call! So!”

Nan’s eyes filled with tears. “No,” she

said faintly.

“Yes!” Cherry marched out, looking

determined.

Nan blew her nose hard. “Oh, dear, what

shall I do?” she said limply.

Sita had been sitting quietly in a corner,

watching and listening. Now she burst into speech.

“Yes! YES!” shouted Nan. “Bus! BUS! –Enough,” she repeated feebly

in Portuguese. “Get me pen and ink, I’ll write a note directly.”

Beaming approvingly, Sita rushed off for

pen and ink.

“Another note from Lady B.’s house,”

explained Bobby helpfully, hovering at Stopes’ side as he brought it into the

sitting-room.

“Bobby, you are a damned nuisance. –Thank

you, Stopes.”

The butler withdrew regretfully.

Bobby came unashamedly to peer over Noël’s

shoulder as he read. “Lor’, Lady B. wants your help in getting rid of Cherry?

What the Devil’s going on, Noël?”

“I shall tell you later,” he said, getting

up. “At least the woman has some decent feeling,” he muttered. “Um—let me see:

where is Aunt Betsy staying, Bobby?”

“With the Dorian Kernohans.”

“Oh—damn. Not at an hôtel?”

Bobby shook his head.

“Hell. It’ll have to be Richard and

Delphie, then,” he muttered.

“For what?”

“For Cherry, and just shut it, I’m

thinking!”

Bobby watched dubiously as his nephew

thought.

“No, damn it,” said Noël. “Enough is

enough. Bobby, I need a respectable female to chaperon Cherry and myself down

to Devon. Think of one.”

“Who, me?”

he gasped.

“Yes. Be of some use for once in your

spoilt life,” said his nephew nastily.

“Here, I say! Uh—well...” Bobby scratched

his curls. “Either of the Miss Careys, I suppose, but Miss Diddy would spread

it all over the town.”

“Quite. And I’m sorry, but not even

Cherry’s reputation would force me to sit with Miss Diddy in a coach all the

way to Thevenard Manor.”

Bobby winced. “No. Er... I think I have it.

What about Miss Sissy Laidlaw? Old enough and respectable enough. I don’t say

she won’t gossip, that’s too much to be expected. But at least she ain’t

covered in bows, dear boy!”

“The woman who looks like a little faded

brown hen?” said Noël with a smile. “I dare say she would do. But does Cherry

like her?”

“Oh, that’s a consideration, is it?” said

his uncle airily.

“Yes, damn your eyes!” he said with a grin.

Bobby scratched his curls again. “Pretty

sure she does. –You should be tellin’ me, y’know.”

“Yes,” he said shortly, going rather red.

“I am aware of that.”

“I’ll go and ask her if she’ll do it, shall

I?” said Bobby helpfully. “That is, if you do intend settin’ off today?”

“I do, yes. Thanks very much, Bobby.”

“Oh, don’t thank me, dear boy, I’m doin’ it

for the thought of Viola’s face, when you and Cherry turn up together!”

“You are in for a disappointment: Viola is

entirely on her side and has been since the moment of first setting eyes on

her.”

“I know that!

What I mean is, her reaction to your draggin’ Cherry half across southern

England in your unsuitable company, with or without a Miss Sissy!”

On

this Bobby went out, sniggering.

Noël had to bite his lip, but he rang for

Stopes and ordered up the travelling coach steadily enough. Then, taking a deep

breath, he hurried upstairs to inform Lady Amory of his intentions. Not to say

of the full story.

Cherry’s plans for the afternoon were

foiled: June was not at home,

“I think she went to call on Mrs

Witherspoon, Miss,” volunteered the little parlourmaid.

“Oh, thank you, Nelly; then I will just—”

“Not Mrs Merry’s ma, Miss Cherry, her aunty!

Mrs Dean!” she gulped.

“Oh, help,” said Cherry limply.

“Yes, Miss. I didn’t know as you was in

Bath, Miss Cherry: welcome back,”

Cherry smiled feebly. “Thank you, Nelly.

Yes, I am staying quietly with Lady Benedict.

“Yes, Miss. I dare say as Mrs Merry, Mrs

Chalfont, I should say, might be back afore too long, if you was wishful to

wait?”

“Um... no, I think not. Please tell her I

called, and I shall call again tomorrow.”

“Yes, Miss Cherry.”

Cherry retreated, frowning a little. There

was no-one else to whom she wished to confide the story: Kitty Hallam was too

silly to listen sensibly and calmly, and, frankly, not nice-natured enough to

believe that Nan and Lord Stamforth were wholly innocent; and Jenny Proudfoot,

though sweet-natured enough not to believe the worst, would not be able to

refrain from telling Mrs Humboldt, who would undoubtedly tell their mamma—and there

was no hope whatsoever that either of these ladies would believe the blameless

version. And though she thought Hortensia Yelden would be sympathetic, she did

not know her well enough to tell her. As for Tarry: she must be very busy, with

the engagement party coming up—and in any case, if she called there, she might

have to face Mrs Henry Kernohan! Cherry shuddered a little, and turned her

steps for Lymmond Square again.

Left to herself, she would have gone along

quite slowly, for there was a considerable number of things which she needed to

think about: but Pug Chalfont, very glad to be out for a real walk at last, was

pulling strongly. Cherry allowed herself to be towed along briskly.

Firmly she decided that once Nan had left

Bath, she would stay with Merry and June while she looked about for a tiny

house which she might possibly be able to afford on her share of her mother’s

estate. Cherry did not feel particularly cheered by her decisions, but by the

time she and Pug rounded the corner into Lymmond Square she did feel very

determined that she would carry them through, and not be a burden to Merry and

June.

“Ooh!” she gasped as Sir Noël jumped out of

a coach just as she reached Nan’s front door.

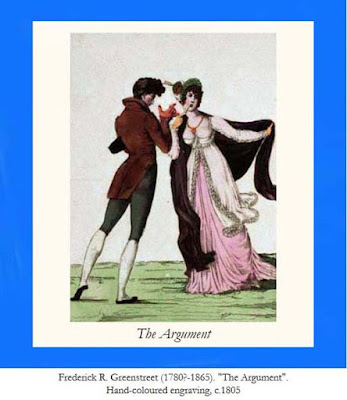

Noël took her elbow tightly. “You are not

going back to Lady Benedict’s house.”

“I AM!” shouted Cherry, turning puce.

“No. She has written me a note asking me to

see that you— QUIET, SIR! SIT!” shouted Noël terribly.

Much abashed, Pug Chalfont plonked his

sturdy hindquarters down hard, and sat up very straight, panting.

“Stamforth has told me the whole, and while

I quite understand that the thing was harmless, no-one else will believe that

for an instant. Lady Benedict herself has written to ask me to keep you out of

it.”

“I do not care! I have told her I will

stick by her, no matter if she does try to send me away!” cried Cherry

defiantly. “And you are not the boss of me!”

“Yes, I am,” said Noël through his teeth.

“And intend to be so in the future. Get into this coach: I am taking you to my

mother.”

“No!” cried Cherry defiantly. “I will not!

And we are not engaged any more, there is no need to pretend—”

“Get into that coach, Cherry, or I shall

put you into it by force!” he said through his teeth.

“Pooh! In the middle of Lymmond Square? You

would not dare!” she cried scornfully.

“Watch me,” said Noël.

He picked Cherry up as if she had weighed a

feather, and deposited her in the coach. As an afterthought grabbing the

half-strangled, wheezing Pug, and slinging him in after her.

“Get going!” he shouted, jumping in and

slamming the door.

The coach set off with a jerk. Noël sat

back in his seat, panting slightly.

“You have half-strangled poor Pug, you

horrible man!” cried Cherry with tears in her eyes.

“Good. You have always loved the damned

creature more than you do me, I wish I had

strangled it!” said Noël violently, not having intended to utter anything so

puerile.

“What?” she gasped.

“You heard,” he said shortly, going very

red.

“You—you are being absurd,” she said

shakily. “He is only a little dog. Of course I love him, buh-but it is not the

same.”

“What is it, then?” said Noël sulkily,

sitting back with his arms crossed.

“It—it— Pug is only a pet,” stuttered

Cherry.

Pug uttered a short yelp.

“Be silent, sir, you are not hurt, only

spoilt rotten!” said Miss Chalfont sharply.

Sir Noël gaped.

“And—and you are sillier than he is!” she

added crossly.

“Uh—yes. Also even more spoilt rotten. It

comes of being an only son, and thus the hope of my family.”

“Mm.”

“Explain to me why, although you love the egregious

Pug, it is not the same.”

Cherry licked her lips nervously. “Pray do

not be absurd.”

“Very well, do not explain,” he said with a

tiny smile. “We shall have plenty of time to figure it out: the journey to

Thevenard Manor will take some days.”

She gulped. “You cannot truly mean— But I

do not have any clothes!”

Noël smiled. “Then you will arrive very

crumpled and grimy. Oh—I see,” he said in a low voice, covering her hand with

his. “There are other necessities you may want, is that it, my darling? Linen,

and so forth?”

Cherry trembled, and was silent.

“Well?” he murmured, putting his head very

close to hers.

“You—you should not speak of such thuh-things,”

said Cherry in a trembling voice. “And—and where is your hat?”

“Eh? Well, I suppose it fell off. Never

mind, Lymmond Square is welcome to it.” He squeezed her hand very hard. “I love

you,” he said conversationally.

“You do not,” said Cherry faintly.

“Of course I do: I would not be eloping

with you, otherwise, you little idiot.”

“You—you are just determined to have your

own way. I will make you a terrible wife,” said Miss Chalfont faintly.

“Very possibly.” Noël untied her bonnet

strings one-handed and pushed the bonnet gently back off the feathery black

curls.

“What are you doing?” said Cherry faintly.

“Endeavouring to convince you that I only

abduct young ladies because I wish to marry them.”

“Stop it,” said Cherry faintly. “I am not

listening.”

“No,”

he agreed vaguely. He bent his head and put his lips on hers.

“Oh,” said Miss Chalfont weakly when he had

stopped.

“I have completely ceased doing that to any

other young ladies,” said Noël. “But unless you continue to let me do it to

you—very, very often—I may backslide.”

“Oh!” cried Miss Chalfont furiously.

“It is the only remedy,” he said, his hand

cupping her chin. “Though not if you did not like it?” He looked searchingly

into her eves.

Cherry’s heart beat very fast; her eyelids

fluttered involuntarily. “Wuh-well, it—it was very strange,” she admitted.

Noël gave a shaken laugh. “Shall we try it

again and see if—if perhaps you could get used to it?”

“Only if you truly, truly want me, because

otherwise I could not bear it,” said Miss Chalfont, looking up at him with

drenched sapphire eyes.

Noël’s own eyes filled. “I truly, truly

want you, Cherry, and I shall never want any other woman again. Please marry

me. I— Please,” he ended lamely.

All on a sudden that sophisticated

man-of-the-world, Noël Amory, did not seem very much older than little Johnny

Edwards to Miss Chalfont. She touched his knee timidly. “Yes,” she said on a

breath.

Noël smiled very, very shakily, and kissed

her tenderly.

“Oh, Sir Noël,” said Miss Chalfont faintly.

“Was that nice?” he said into her neck.

“Yes.”

“Good. Hold me tight,” he said into her

neck.

Cherry put her arms round him and held him

very tight.

“Never let me go,” said Noël, after a

considerable period of silence had

passed.

“No,” she agreed.

“I mean it,” he said, sitting up a little

and looking anxiously into her face. “I need you terribly, Cherry. And—and if I

do or say anything that you do not like, please tell me, and I will rectify

it.”

Cherry smiled shyly. “Yes, very well. And

please tell me if—if I do things wrong.”

“I assure you could not do anything wrong!”

he said with a little laugh.

“No—um—well, you know,” she said, suddenly

becoming terribly flustered. “Things!”

“Er—oh! Things!” said Noël, laughing. He

kissed her again, very long and lingering. “This sort of thing?” he murmured.

“Well, yes.”

“Very fortunately we have the rest of our

lives to practise it.”

“Yes,” said Cherry faintly, blushing

brightly.

“But I am afraid,” said Noël, peering out

at the street, “that just for the moment we shall have to halt the practice

session.’

“Where are we?” said Cherry in bewilderment

as the coach drew up.

“At Miss Sissy Laidlaw’s. She will be

chaperoning us to Thevenard Manor. –I hope you do not mind?”

“Oh, no, I should love to have her

company!” she cried.

“Good,” said Noel, kissing her ear. “But

just for tonight we shall only go as far as Doubleday House. I dare say Delphie

will be able to help you with linen and so forth.”

“Of course. I mean—” Cherry drew a deep

breath. “You should not speak of such things until we are married,” she said

severely.

Noël’s sherry-coloured eyes twinkled. “Very

well. But after we are married, I warn you, I shall show no mercy!”

Very strangely, at this severe, indeed

high-handed utterance from Sir Noël Amory, Miss Chalfont collapsed in a

helpless fit of the giggles.

No comments:

Post a Comment